Consideration of Preferred Learning Styles in the Module PSYC3646

(Forensic Psychology in Practice)

by Dr Gill Harrop, Lecturer in Forensic Psychology, Institute of Health and Society

and Dr Dean Wilkinson, Senior Lecturer, Institute of Health and Society

Dunn et al. (1995) found that matching students’ learning-style preferences to teaching strategies is beneficial to academic achievement, while Yassin and Almasri (2015) suggested that failing to consider students’ differing preferred learning styles can lead to students disengaging and feeling confused. In an effort to address this issue, learning preferences within PSYC3646 (Forensic Psychology in Practice) were considered within the context of Jahiel’s VAK model (2008), which identifies visual, auditory and kinaesthetic learning preferences. This model was selected due to positive reviews within the pedagogical literature around the benefits of using VAK within an education setting (Willis, 2017; Fleming and Baume, 2006) and its wide use within schools, universities and teacher training institutions in England and Wales (Sharp, Bowker and Byrne, 2008).

We actively sought to accommodate different preferred learning styles across our teaching activities within this module. One example of this was a workshop on restorative justice, where the students completed individual reflection worksheets which mirrored a task that a young offender might be given within a one-to-one session. Discussion-based activities were then used to reflect on the potential uses of the worksheet in practice, followed by a didactic teaching session using a PowerPoint presentation, and analysis of an abstract from a recent publication, which the students read themselves before discussing it in small groups.

The final activity involved splitting the students into pairs and assigning one to be the ‘psychologist’ and one to be the ‘offender’. Students were advised that the ‘offender’ would be reading a short case study and then describing an offence, and the ‘psychologist’ would be listening and drawing. This allowed them to each pick the role that they felt most suited to. The ‘psychologist’ was given a piece of blank A4 paper, folded into 9 squares, and the task for each pair was to produce a storyboard of the offence, drawn out by the ‘psychologist’. This required the ‘offender’ to describe their offence (based on the case study description they had been given) to the ‘psychologist’, who then drew out the offence as a storyboard. The aim of the task was to help the ‘offender’ reflect upon the offence.

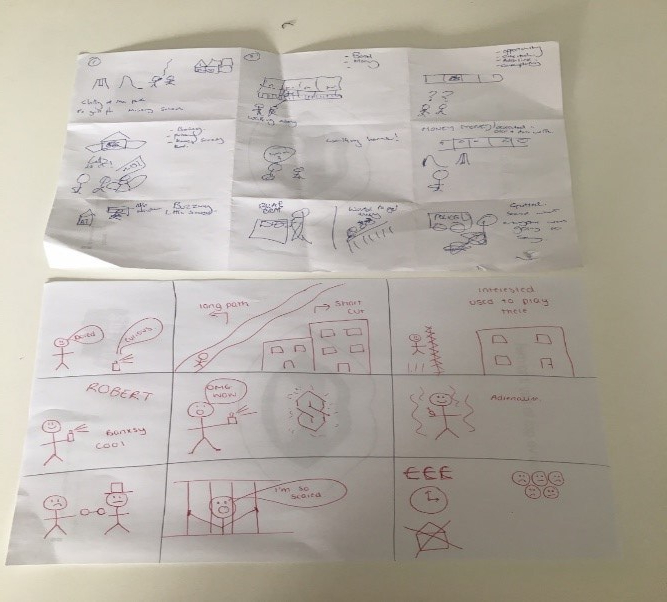

At the end of the task, the ‘psychologist’ in each pair described the storyboard to the class. Two examples of storyboard drawings from this activity are shown in Figure 1. The range of activities offered within this workshop (reading from academic literature, completing a questionnaire, discussion tasks, short lecture, describing a case study and drawing out the storyboard) ensured that all students had the opportunity to engage in tasks that matched their preferred learning style at some point in the workshop.

Figure 1. Student storyboard activity

Feedback from the workshop was very positive and students noted that the activities had helped them to remember what they had learnt, particularly the storyboard activity. Several students were still able to recount what they had learnt from this session, including their case study example from the storyboard activity, even though several weeks had passed, suggesting the range of activities had a positive impact upon student retention as well as engagement.

We continually evaluate the effectiveness of our approach through module evaluation forms, in-class focus groups and feedback from course committee. Feedback has been very positive, with the last module evaluation for PSYC3646 achieving 100% student satisfaction. The impact of our teaching also feeds into the National Student Survey results for the forensic psychology programme, and we were extremely proud to achieve 100% student satisfaction in the 2017 NSS. In addition, forensic psychology has consistently performed well at the Student Choice Awards, with a forensic psychology module being selected as the top module in our Institute for the last three years.

References

Dunn, R., Griggs, S. A., Olson, J., Beasley, M., & Gorman, B. S. (1995). A meta-analytic validation of the Dunn and Dunn model of learning-style preferences. The Journal of Educational Research, 88(6), 353-362.

Fleming, N., & Baume, D. (2006). Learning Styles Again: VARKing up the right tree!. Educational developments, 7(4), 4.

Jahiel, J. (2008). What’s your learning styles? Practical Horseman, 36(3), 32-37.

Sharp, J. G., Bowker, R., & Byrne, J. (2008). VAK or VAK‐uous? Towards the trivialisation of learning and the death of scholarship. Research Papers in Education, 23(3), 293-314.

Willis, S. (2017). Literature review on the use of VAK learning strategies. The STeP Journal, 4(2), 90-94.

Yassin, B. M., & Almasri, M. A. (2015). How to accommodate different learning styles in the same classroom: Analysis of theories and methods of learning styles. Canadian Social Science, 11(3), 26.